Carnivore Ecology

I have been fortunate enough to work with several predator species during my career - black-footed ferrets, skunks, raccoons, and now bobcats - and feel very fortunate to study this special group of animals. Mesopredators are adaptable, have complex social boundaries, and are extremely important in the balance of our ecosystems. They also face many threats worldwide and over half of mesopredator species are in decline. Despite this, they are often overshadowed by larger, more charismatic species.

In the southeastern US, barrier islands dot the coastline. These islands support numerous species of plants, fungi, birds, reptiles, and mammals including mesopredators - including the bobcat! These islands are also attractive to people due to their beauty and human development often directly borders valuable wildlife habitat.

The catalyst for my research was a recent discovery of second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides exposure in the bobcat population on Kiawah Island (Charleston County, SC). These bobcats have been monitored since the early 2000s, so biologists were able to identify a decline in the population and investigate. Non-target anticoagulant rodenticide exposure is not unheard of, however it is severely understudied in the Southeastern U.S. and studies that do exist are limited in geographic scope.

The scope of my study is to analyze historical data and identify shifts is space use and survival in the Kiawah bobcats from the early 2000s to now. Additionally, I will continue monitoring the Kiawah population as well as a second population of bobcats on a barrier island in Georgetown County, SC. By comparing these populations, I hope to pinpoint behavioral and dietary differences potentially influenced by anticoagulant rodenticides and human development.

Recent News:

In the southeastern US, barrier islands dot the coastline. These islands support numerous species of plants, fungi, birds, reptiles, and mammals including mesopredators - including the bobcat! These islands are also attractive to people due to their beauty and human development often directly borders valuable wildlife habitat.

The catalyst for my research was a recent discovery of second-generation anticoagulant rodenticides exposure in the bobcat population on Kiawah Island (Charleston County, SC). These bobcats have been monitored since the early 2000s, so biologists were able to identify a decline in the population and investigate. Non-target anticoagulant rodenticide exposure is not unheard of, however it is severely understudied in the Southeastern U.S. and studies that do exist are limited in geographic scope.

The scope of my study is to analyze historical data and identify shifts is space use and survival in the Kiawah bobcats from the early 2000s to now. Additionally, I will continue monitoring the Kiawah population as well as a second population of bobcats on a barrier island in Georgetown County, SC. By comparing these populations, I hope to pinpoint behavioral and dietary differences potentially influenced by anticoagulant rodenticides and human development.

- More information can be found on my project website, which further outlines the project goals, partners, and includes links to similar research: Island Bobcat Research

Recent News:

- Graduate Student Highlight by the Clemson Department of Forestry and Environmental Conservation (Mar. 4, 2024)

- Article by the Decipher Creative Inquiry Magazine (Nov. 3, 2023)

- Newsletter Feature by the USGS Western Ecological Research Center (Apr. 20, 2023)

- Newsletter Feature by the Wildlife Society Southeastern Section (Feb. 20, 2023)

- News highlight by ABC 4 Charleston (Oct. 12, 2022)

- Quarterly Report by the Town of Kiawah Island (Aug. 24, 2022)

- Article by the Town of Kiawah Island (Feb. 1, 2022)

- Article by the Town of Kiawah Island (Aug. 6, 2021)

Movement Ecology

Animal movement is one of the most interesting aspects of ecology (my opinion). Understanding where they are and why is a great step in seeing inside the mind of an animal! For some, resource selection seems simple - but for others, it can answer complex questions about metabolic needs, temporal and seasonal behavior, and the cultural nature of some species.

While working on a long-term waterfowl project in Suisun Marsh in California, I was able to gain first-hand experience tagging and tracking ducklings. While ducklings themselves may not always make conscious choices about their movement and habitat selection, we can learn a lot about their metabolic limitations. As it turns out, they are able to adapt to changing landscapes - to a point. Understanding where these points occur gets us closer to understanding waterfowl breeding ecology and management needs. We also deployed transmitters on adult hens, Northern Harriers, and common nest predators (skunks and raccoons).

For my master's research, we had nearly a decade of animal location data - enough to draw conclusions about trends in movement, resource selection, and behavior. Linking behavior requires more data and uses different methods - it's really cool! If you have an interest in animal movement, either practically or on an analytical level, feel free to reach out!

Recent News:

While working on a long-term waterfowl project in Suisun Marsh in California, I was able to gain first-hand experience tagging and tracking ducklings. While ducklings themselves may not always make conscious choices about their movement and habitat selection, we can learn a lot about their metabolic limitations. As it turns out, they are able to adapt to changing landscapes - to a point. Understanding where these points occur gets us closer to understanding waterfowl breeding ecology and management needs. We also deployed transmitters on adult hens, Northern Harriers, and common nest predators (skunks and raccoons).

For my master's research, we had nearly a decade of animal location data - enough to draw conclusions about trends in movement, resource selection, and behavior. Linking behavior requires more data and uses different methods - it's really cool! If you have an interest in animal movement, either practically or on an analytical level, feel free to reach out!

Recent News:

- Newsletter Feature by the USGS Western Ecological Research Center (Apr. 20, 2023)

Avian Ecology

I started my career as a waterfowl technician in southern Colorado, and then spent the few years prior to graduate school as a waterfowl technician in the San Francisco Delta region of California. As a casual birder and lover of long-term datasets, the waterfowl field has always been of interest to me. My research background has also expanded into songbirds and scavengers.

Birds are unique in that they can span multiple continents within their lifetime or even their annual movements. They unite governments and interest groups, and, for many people, are often the earliest introduction to wildlife. I find their conservation to be of the utmost importance as indicators of ecosystem health and a valued natural resource. They also reveal areas of conservation need through their long-distance movements!

I am primarily interested in breeding ecology and habitat use, as well as inter-species interactions with predators and competitors. I have made use of historic datasets, novel datasets, and eBird data to look into avian response to predators, climate change, habitat degradation, and spatial ecology.

Recent News:

Birds are unique in that they can span multiple continents within their lifetime or even their annual movements. They unite governments and interest groups, and, for many people, are often the earliest introduction to wildlife. I find their conservation to be of the utmost importance as indicators of ecosystem health and a valued natural resource. They also reveal areas of conservation need through their long-distance movements!

I am primarily interested in breeding ecology and habitat use, as well as inter-species interactions with predators and competitors. I have made use of historic datasets, novel datasets, and eBird data to look into avian response to predators, climate change, habitat degradation, and spatial ecology.

Recent News:

- Guest Blog through The Wilson Ornithological Society (Dec. 19, 2023)

- Newsletter Feature by the USGS Western Ecological Research Center (Apr. 20, 2023)

Quantitative Ecology

I developed an interest in quantitative ecology during my undergrad studies at Colorado State University. After several field seasons post-graduation, my interest was strengthened as I learned about the many large datasets gathered over the years within various agencies and among different study areas. These datasets often sit idle due to a lack of expertise and/or time to commit to learning new methods, so I decided to take a crack at one myself. One can also argue that the quick publication turnaround to justify grant funding can inhibit researchers' ability to contribute to long-term studies, but that's another discussion.

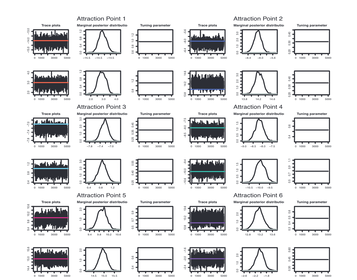

After several years of technician work, I joined Dr. William's quantitative ecology lab at the University of Nevada, Reno. While there, I was able to work with a mule deer GPS collar dataset gathered over eight years in Mojave National Preserve in southern California. These data consisted of about 200 animals and just under one million locations. Despite being analyzed in chunks as it was collected, there were, and always will be, unanswered questions. Over the span of my master's degree, my time was spent developing a Bayesian hierarchical model to describe animal movement in relation to landscape features, with the goal of increasing resource managers' understanding of the importance of these landscape features while also adding to the movement ecology literature through model development.

Despite primarily working in a Bayesian framework, my curriculum was dominated by courses in the Mathematics and Statistics department so I am able to interpret and implement frequentist analyses as well. If you are in interested in quantitative ecology, or any type of data science, please feel free to reach out to me!

After several years of technician work, I joined Dr. William's quantitative ecology lab at the University of Nevada, Reno. While there, I was able to work with a mule deer GPS collar dataset gathered over eight years in Mojave National Preserve in southern California. These data consisted of about 200 animals and just under one million locations. Despite being analyzed in chunks as it was collected, there were, and always will be, unanswered questions. Over the span of my master's degree, my time was spent developing a Bayesian hierarchical model to describe animal movement in relation to landscape features, with the goal of increasing resource managers' understanding of the importance of these landscape features while also adding to the movement ecology literature through model development.

Despite primarily working in a Bayesian framework, my curriculum was dominated by courses in the Mathematics and Statistics department so I am able to interpret and implement frequentist analyses as well. If you are in interested in quantitative ecology, or any type of data science, please feel free to reach out to me!